[cross-post from Pocket Change]

Joseph Cowell (1792-1863) was a British comedian and theatrical entrepreneur who performed on both sides of the Atlantic. His memoir, Thirty Years Passed Among the Players (1844), offers a fascinating window into the nineteenth-century entertainment industry, and includes some interesting anecdotes relating to numismatics as well. Born Joseph Hawkins Witchett, he started out as a sailor before a series of mishaps and adventures led him to a life on the stage. Adopting the stage name Cowell, Joe first appeared on stage in London, where he gained renown as a comedian and became a favorite at the famed Theatre Royal, Drury Lane.

This eventually brought Cowell to the attention of Stephen Price and Edmund Simpson, the lessees and managers of New York City’s Park Theatre. When it initially opened January 1798, it was simply known as “The Theatre” as it lacked any real competition. This particular building is actually well-known to numismatists as it features on the much-debated “Theatre at New York” token.

In John Kleeburg’s definitive essay on the token, he shows that it is the work of Benjamin Jacob, a Birmingham diemaker who copied the design from an illustration of the theatre under construction that was published in the 1797 edition of Longworth’s American Almanack . The theatre struggled during its early years, but eventually found its feet in the 1810s and 1820s under the able management of Simpson and Price.

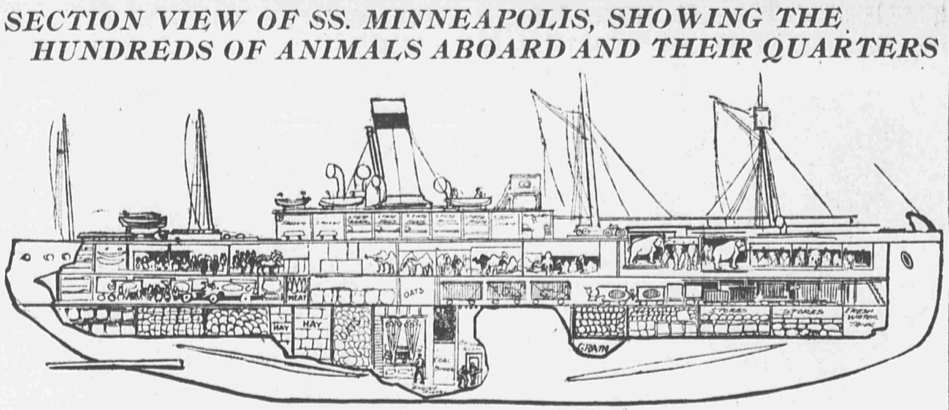

The formula that proved most successful was simply to import the best talent they could find from Britain each season, a strategy that brought the likes of James W. Wallack (1818-19), Edmund Kean (1820-21), and other stars across the Atlantic. The original Park Theatre burned to the ground in May 1820, but a new theatre financed by John Jacob Astor was constructed on the same site.

![Second Park Theatre [first building to right], 1831 New York Public Library](http://www.anspocketchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/PT-18311-1024x568.jpg)

New York Public Library

Cowell came off the ship eager for a meal, but found that New York City in those days was not exactly accommodating for travelers. With “thirteen or fourteen English shillings” in his pockets, he roamed the streets look for a place to eat:

After wandering about I knew not whither, “oppressed with two weak evils,” fatigue and hunger, I entered what in London would be called a chandler’s shop, put some money on the counter, and inquired if they would sell me for that coin some bread and butter and a tempting red herring or two I saw in a barrel at the door.

“Why, what coin is it!” said a fellow in a red-flannel shirt and a straw hat.

“English shillings,” I replied.

“No,” said the fellow, “I know nothing about English shillings, nor English anything, nor I don’t want to.”

I thought, under all the circumstances, and from the appearance of the brute, it might be imprudent to extol or explain their value, and therefore I “cast one longing, lingering look behind” at the red herrings in the barrel, and turned the corner of the street, where I encountered two young men picking their teeth, for which I have never forgiven them.

Cowell blamed the difficulty of this encounter on the late war with England, which he believed was “still rankling the minds of the lower orders of Americans.” He then went in search of a place to exchange his shillings, eventually heading up Broadway and coming upon “a dingy-looking cellar” with a sign reading: “Exchange Office. Foreign gold and silver bought here.” Cowell depicted the scene as follows:

I descended three or four wooden steps, and handed my handful of silver to one of “God’s chosen people,” and, after its undergoing a most severe ringing and rubbing, the (I have no doubt) honest Israelite handed me three dirty, ragged one-dollar bills, which, he said, “s’help me God is petter as gould.” As all I wanted then was that they should be better than silver, my politics at that time didn’t cavil at the currency, and I hastily retraced my steps to the red-shirted herring dealer, and, placing one of the dirty scraps of paper on the counter, I exclaimed, with an air of confidence, “There, sir, will that answer your purpose?” He was nearly of the Jew’s opinion, for he declared that it was “as good as gold,” and I gave him a large order, and made my first meal in the United States seated on a barrel, in a grocery at the foot of Wall-street.

There is a lot to unpack here, from the casual anti-Semitism to the larger workings of the American monetary system. The essential problem was that the United States at the time lacked the domestic sources of gold and silver necessary to produce enough coins to satisfy its growing populace. The 1820 census showed that the population was nearing ten million, but the U.S. Mint only produced two million silver coins that year in all denominations (10¢, 25¢, and 50¢) and the only gold coins minted were a quarter of a million half eagles ($5). This was obviously not anywhere near enough coinage, so the balance of circulating money consisted of Spanish silver coins and, particularly in urban contexts, paper money. The “dirty dollars” that Cowell exchanged his shillings for would have looked something like this two-dollar bank note from the Franklin Bank of New York City:

At the time, banks issued what was essentially their own currency, which was printed with variable quality and rather quickly became ragged as it circulated. Paper money was also easily counterfeited, and the issuing banks were themselves often suspect, making for a confusing swirl that could leave the unsophisticated bereft. Cowell’s aside that “his politics at the time didn’t cavil” at paper money suggests that he later became an advocate of “hard money” (i.e. specie), perhaps due to some bad experiences with the paper kind.

As historians like Shane White and Timothy Gilfoyle, among others, have shown, new arrivals to the city were often marks for various sorts of unscrupulous characters looking to turn a quick buck. Many of New York City’s so-called “exchange offices” existed in the grey area at the margins of the financial industry, making their money in quasi-legal lottery and stock schemes. As their name suggests, they also functioned as domestic and international currency bureaus, giving out local paper money for foreign coin or bank notes from elsewhere in the United States, at widely variable rates. Whether or not he got a fair exchange from the stereotypical Jewish money changer he encountered, Cowell ended his first day in New York City flat broke through more traditional means.

After his meal, Cowell dropped in for an unimpressed look at the evening’s entertainment at the Park Theatre. Later, he found his way to the bar and treated some new American friends to a few rounds of grog and cigars. He eventually became so incapacitated that he was robbed of all of his “moveables,” which included his “hat, cravat, watch, snuffbox, handkerchief, and the balance of the dirty dollars.” Cowell was subsequently carried down to the harbor, tossed into a row boat, and delivered to the ship he had arrived on as “a gentleman very unwell.”

Despite Cowell’s inauspicious start, he had a very long and successful career in the United States. He made his debut at the Park Theatre on October 30, 1821, and was particularly well received for his performance as Crack in the musical The Turnpike Gate. Cowell went on to become one of the most popular stock players at the Park when the theatre was at the apogee of its profitability and influence in the 1820s. He ably managed a variety of companies and theatres around the country, and spent some time in the circus as well. Cowell married three times and many of his descendants, most notably Sam Cowell and Kate Bateman, became luminaries in Anglo-American theatre. He reprised the role of Crack for his final performance in New York City in 1863 before retiring to London. Cowell’s memoir is a wonderful read that offers a compelling look at the world of popular entertainment while also observantly noting and commenting on the particulars of everyday life in the United States.