Opinion column for the New York Daily News, published February 16, 2014.

The times are changing.

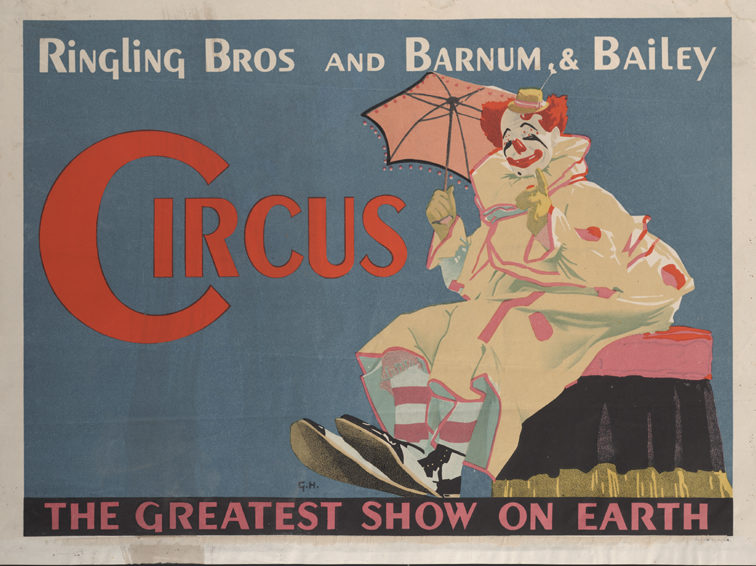

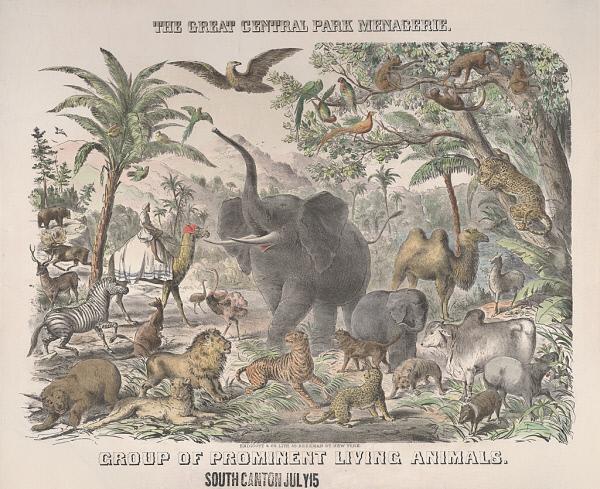

The arrival this week of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus at Barclays Center has prompted a renewed push by animal welfare advocates for the city to ban wild or exotic animals like elephants and lions in public entertainments.

Having studied the history of circuses nationally and in New York, and understanding the evolution of this particularly American spectacle, I support the ban — not because I loathe the circus, but because I know it intimately and, for the most part, love it.

The City Council has previously proposed bills that would have effectively prohibited circuses from using exotic animals in their New York shows — and momentum seems to be building for a ban now. Animal rights groups like NYCLASS, which has been instrumental in the effort to end the use of carriage horses in Central Park, have undoubtedly been emboldened by Mayor de Blasio and Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito’s past support of such legislation and the broadening public concern for animal welfare.

The Ringling show and other American circuses that employ more traditional big cat acts and performing elephants are of course adamantly opposed, insisting that their animals are well cared for and offer audiences a unique blend of education and entertainment.

Those who protest the circus outside of Barclays or grimace as they take their children inside the arena despite the signs need to understand the historical context.

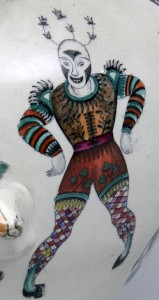

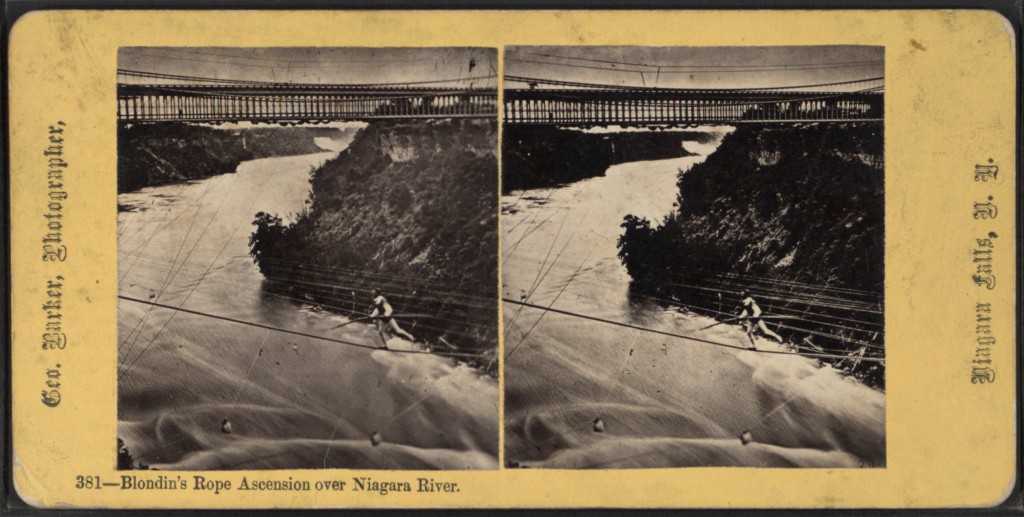

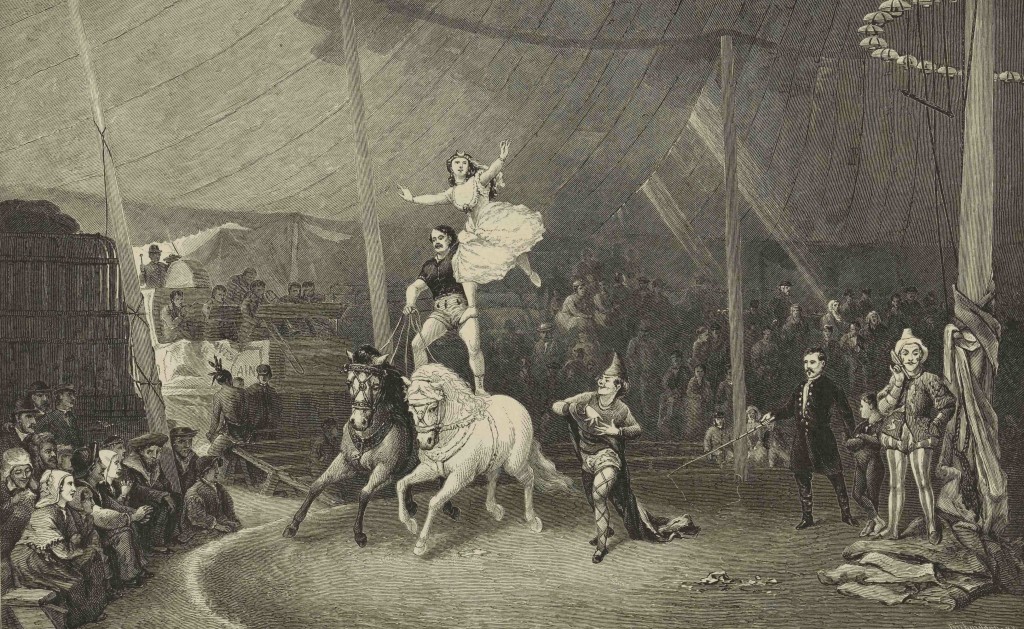

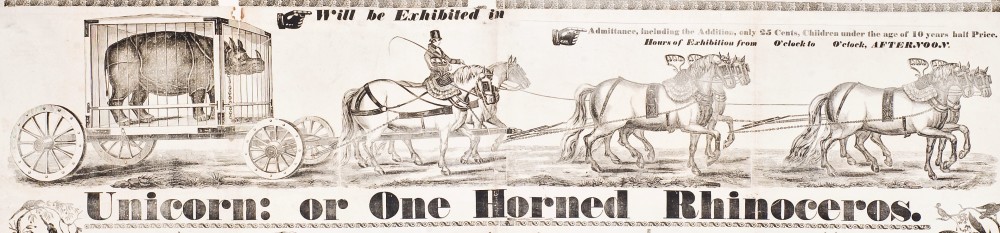

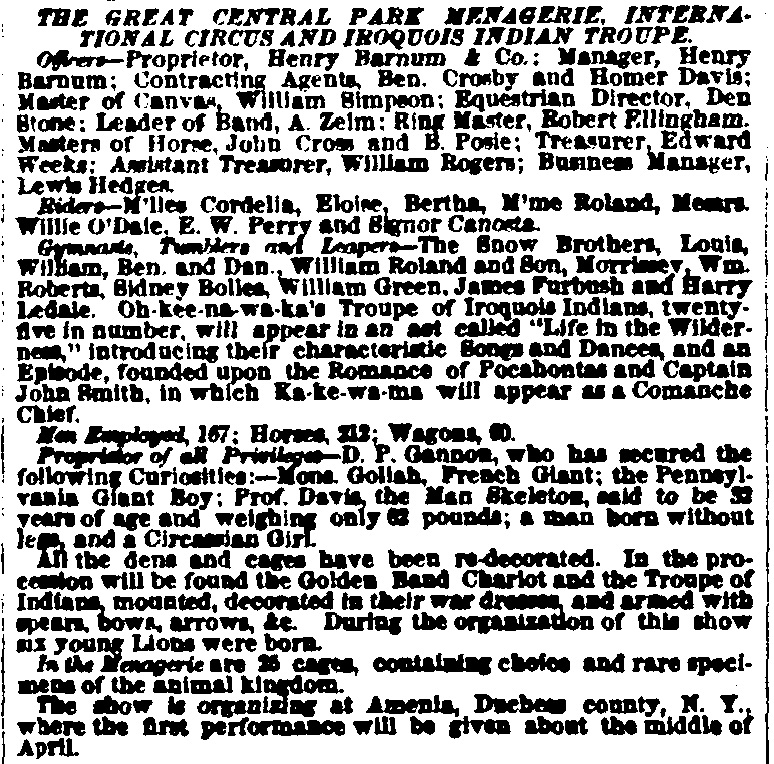

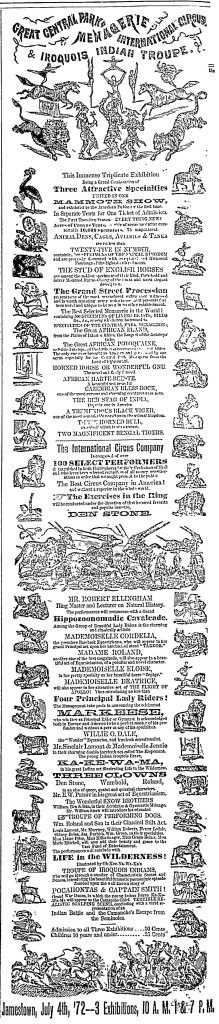

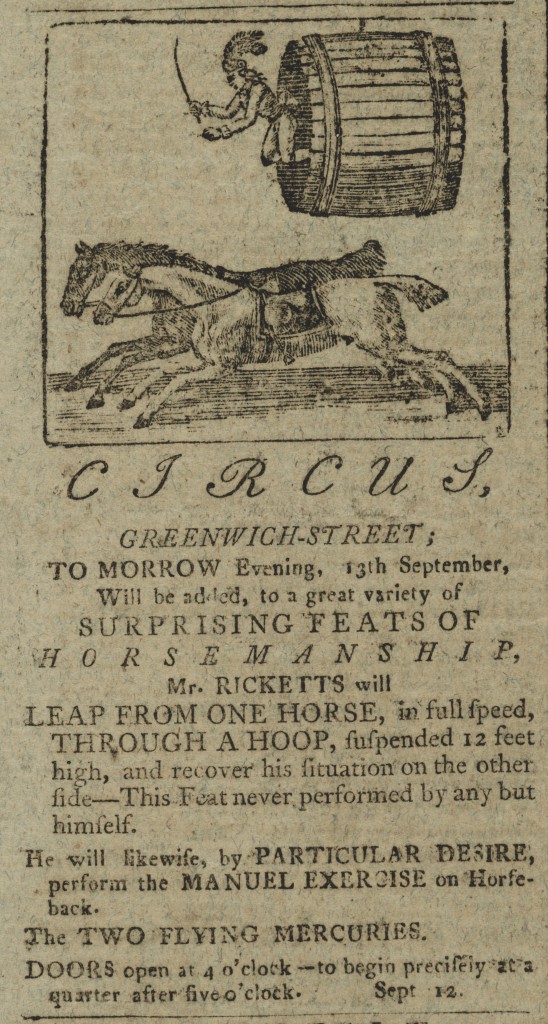

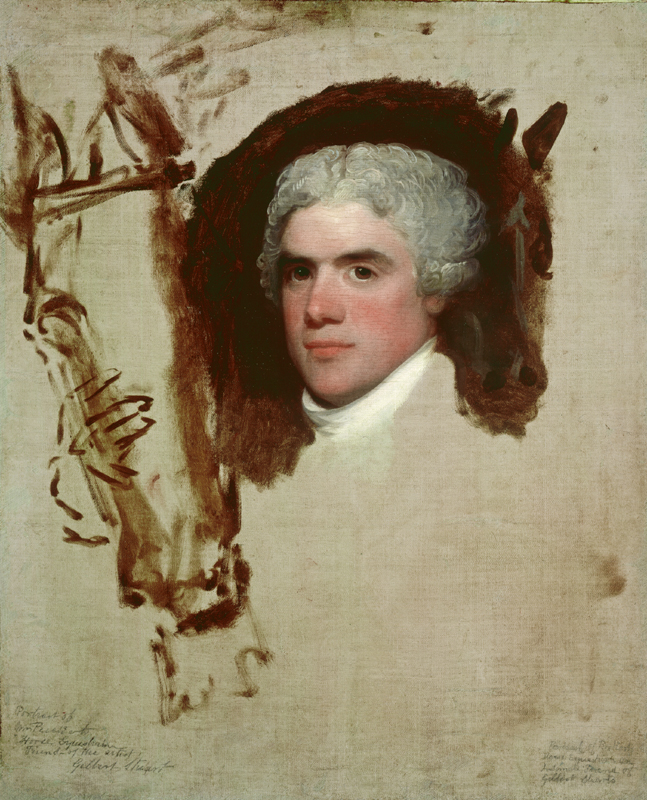

This debate over the use of animals in popular entertainment is a long-running one, extending back to at least the late 18th century, when exotic-animal exhibitions flourished and the acrobat and rider John Bill Ricketts established the first circus in New York City. In the decades that followed, traveling shows featuring a panoply of daring performances and wild animals became so numerous and popular that Walt Whitman declared the circus “a national institution.”

The circus was not immune from controversy or criticism, with much of the opposition rooted in religiously motivated concerns about the perceived immorality of the performers and the treatment of the animals. Isaac Van Amburgh found fame and fortune in the 1830s by becoming the first trainer to enter the cages and perform with the lions and tigers, the so-called big cats. While many found his performances thrilling, others were horrified by their brutality as Van Amburgh regularly thrashed his animal charges with a metal bar in the course of the act.

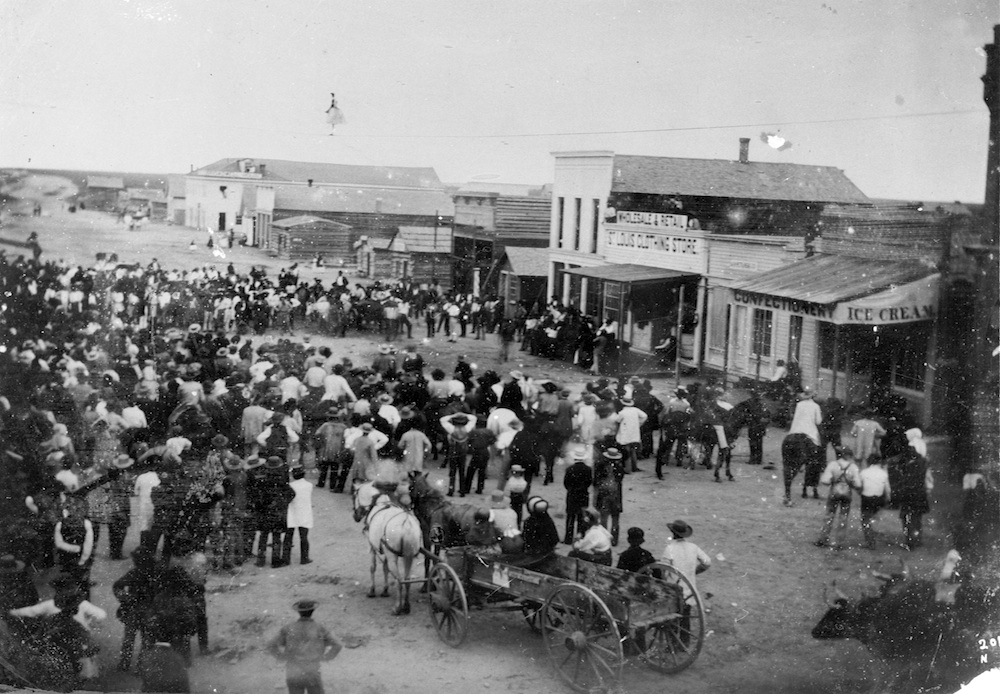

Opposition to the circus was ultimately ineffectual, and by the late 19th century it was perhaps Americans’ favored form of entertainment, with hundreds of traveling shows of all sizes crisscrossing the country every year.

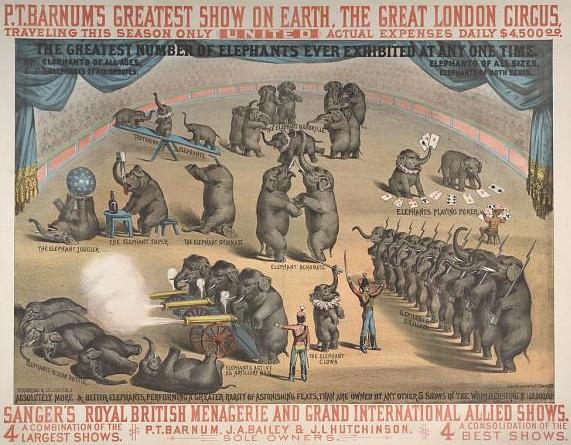

And yet sporadic debates over the treatment of animals persisted, particularly in New York City, where the founding of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals by Henry Bergh coincided with the rise of P. T. Barnum’s celebrated circus.

Bergh and Barnum fought a series of battles, most notably in 1880 over an act by a horse called Salamander that jumped through flaming hoops and fireworks. But the occasional controversy only seemed to draw more people in.

Incidents such as the 1902 public execution by choking of an unruly Barnum & Bailey elephant named Mandarin along the city docks provoked an outcry, but it was not until the 1920s that organized activist pressure led John Ringling and other circus owners to begin dropping or altering acts that suggested cruelty.

And so, the sharp disagreements and protests occasioned in more recent years by the annual visit of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus to the New York area are just the latest iteration of a long-running struggle. What’s different — and ironic — is that, despite undeniable improvements in the conditions of many of the animals, advocates for animal welfare finally seem to be winning the argument.

That the venerable Big Apple Circus now almost exclusively employs domestic animals like dogs and horses is a good indication of this trend, as is the near-absence of animals in Cirque du Soleil, Circus Oz and other circus-inspired shows that frequent the city.

Increasing public concern about animal welfare has arguably led American circuses to institute some constructive changes in their treatment of animals. But the massive fine the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus paid to the USDA in 2011 for violations of the Animal Welfare Act suggests that serious issues persist.

Moreover, the fact is that many people, myself included, believe that wild animal acts are outmoded and often cruel. We find the sight of circus elephants being put through their paces — beautiful, large and intelligent creatures compelled to perform silly acts to cheering crowds — troubling.

My own opposition is rooted in a moral conviction that the dignity and well-being of wild animals is fundamentally at odds with forcing them to perform for our entertainment. Whatever its source, it is a feeling that is widely shared, as bans on the use of circus animals are being implemented the world over, with India and the United Kingdom among the most recent to adopt prohibitions.

You need only witness the intense, passionate reaction to Blackfish, the documentary story of Seaworld’s killer whale Tilukum, to understand that a new moral imperative is spreading in the air, and the water.

Public relations efforts and appeals to tradition by defenders of the circus cannot shield from scrutiny practices that so many people in this city and around the world now find inhumane. The standards for what constitutes animal welfare for mainstream Americans have and will continue to evolve, but a serious reconsideration of using wild animals in the service of commercial entertainment is clearly underway — and the prospective ban on exotic and wild animals in New York City is part of this process.

As a circus fan and historian, I can only hope that the holdouts grasp this ongoing shift and abandon the use of wild animals in favor of the spirit of innovation that allowed the American circus to flourish in the first place.

If they do not, then it is high time for animal welfare advocates and their allies at City Hall to act.

Tunstall was part of the so-called “Staffordshire Potteries” (modern-day Stoke-on-Trent), a center of ceramic production that developed in the late seventeenth century and which became a hotbed of

Tunstall was part of the so-called “Staffordshire Potteries” (modern-day Stoke-on-Trent), a center of ceramic production that developed in the late seventeenth century and which became a hotbed of