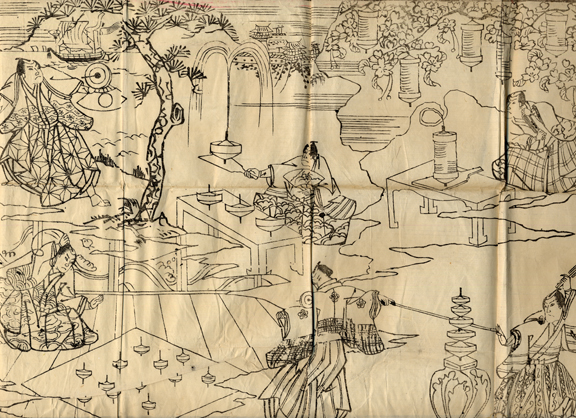

In an earlier post about the American statesman John Hewson Pruyn, I wrote about the role that the American circus performer and impresario Richard Risley Carlisle played in the evolving cultural relationship between the United States and Japan. Risley arrived in Yokohama on March 6, 1864 with a small troupe of performers, and Pruyn initially expressed hope that the circus would help thaw tensions between the Japanese and foreign communities. The show opened on March 28 in front of an audience of around four hundred people, about half of whom were foreign residents. Pruyn was seemingly less than impressed with the circus as a letter dated April 1 noted that “the Japanese admire the clown very much,” but that he was “the very poorest I ever saw.” He went on to sarcastically speak of the relatively expensive tickets as being “exceedingly cheap for so intellectual a performance.” Whatever Pruyn’s opinion, the circus proved popular and a number of Japanese artists made wonderful woodblock prints documenting the show, including this one by Utagawa (or Issen) Yoshikazu.

After its initial success, interest in the circus waned and the performers dispersed, but Risley elected to stay in Japan and pursued a variety of eclectic ventures, including at one point importing dairy cows from California and selling ice cream (for more on Risley’s doings in Japan, see Frederik Schodt’s aforementioned book). But the big idea that he finally hit upon was the realization that the Japanese performers who often entertained the foreign community would be a real novelty abroad. Indeed Pruyn frequently commented on the quality of Japanese entertainment, and he was particularly taken with the characteristic top-spinning performances that he witnessed, which were a novelty to foreigners. Below is a woodblock print that Pruyn saved commemorating a November 14, 1864 performance by a famous top-spinning troupe headed by Matsui Gensui (for a full account of the evening see Francis Hall’s recently published journal).

Woodblock print

1865

Albany Institute of History & Art

Robert H. Pruyn Manuscript Collection, CH 532

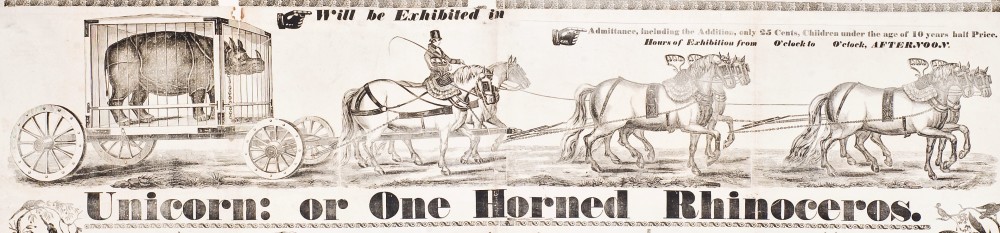

Matsui Gensui and those of his ilk were known as misemono, which Schodt translates literally as “things to show” or “exhibitions,” and included sleight-of-hand, balancing, juggling, acrobatics, amongst a range of other entertainments. The obvious popularity of misemono amongst the foreign community led a number of would-be impresarios to consider organizing a troupe to tour abroad, but the Japanese government’s prohibition on overseas travel and raising the necessary capital made such a venture difficult. With the help of the U. S. consul and local American merchants, Risley cobbled together the needed funding and secured permission for what was dubbed the “Imperial Japanese Troupe” to head abroad. In early 1867, the troupe arrived in San Francisco and embarked on a strikingly successful tour across the United States and eventually around the world. As Schodt notes, Risley’s Imperial Japanese Troupe ultimately played a signature role in introducing the then mysterious world of Japan to those in the West. Risley’s activities are a more or less perfect distillation of one of the major themes of my own work, namely how popular entertainment has served as a medium for cross-cultural exchange.

Though we are straying ever farther from Robert Hewson Pruyn, the man whose papers at the Albany Institute of History & Art originally inspired these posts, I want to highlight one last cultural artifact of interest. It is a short motion picture filmed in Thomas Edison’s New York Studio on April 29, 1904 now at the Library of Congress. It shows two Japanese acrobats performing what was by then known simply as a Risley act. It was this foot-juggling routine that catapulted its namesake to fame and fortune, and its performance by two Japanese entertainers aptly illustrates the ongoing legacy of international exchange via performance and popular culture.