An eagle-eyed reader sent me a photograph of a gravestone they spotted in Oakwood Cemetery in East Aurora, New York. It memorializes George G. Gordon, who died on June 11, 1872. The stone is graced with a wonderfully cut illustration of a large circus tent, inside of which an inscription reads:

Erected by Henry Barnum

and the members of the Central

Park Menagerie and Circus.

In memory of

GEORGE G. GORDON

who departed this life June 11, 1872

In the 31 Year of his Age.

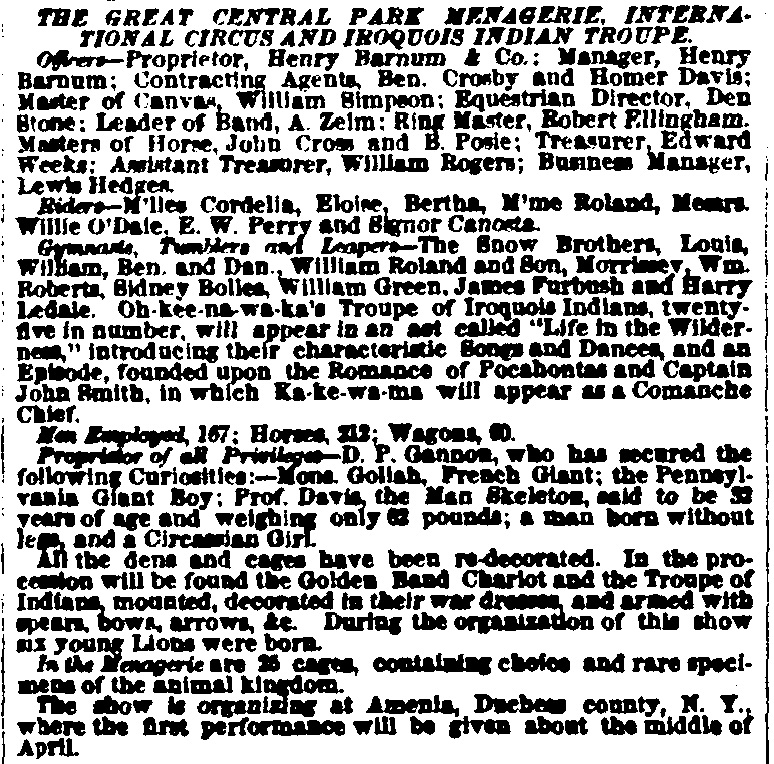

The Great Central Park Menagerie and Circus was a short-lived show that was organized over the winter of 1871-72 in Amenia, New York. The proprietor and manager of the operation was Henry Barnum, a longtime circus man and distant relative of the showman P. T. Barnum. Dennison “Den” Stone was the equestrian director and coordinated the riding acts, which were the primary draw for the circus in that era. In its spring preview of the “tenting season,” the New York Clipper gave the following summary of the show:

As you can see by the fact that 167 men, 212 horses, and 90 wagons were employed, it was a labor-intensive wagon show that was hauled overland each night and set up in a new location for two or even three performances each day. The Great Central Park Menagerie and Circus was one of the largest wagon circuses to ever tour, as it was put together just as railroads were transforming the show world. Indeed it was in this same year, 1872, that P. T. Barnum’s famous circus toured by rail for the first time, and by the end of the decade all the biggest shows had abandoned wagon travel for railroads.

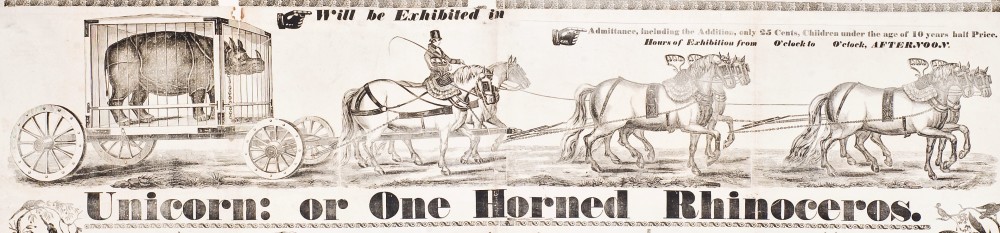

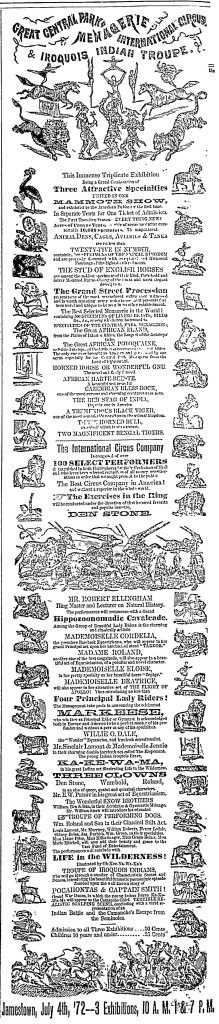

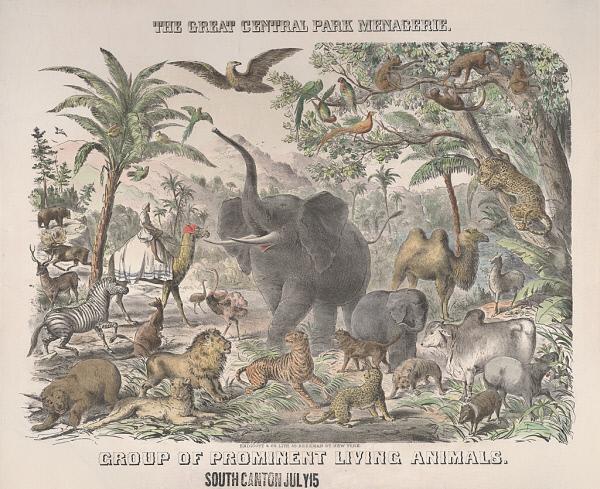

The Great Central Park Menagerie, International Circus, and Iroquois Indian Troupe toured through western Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont in April and May, and then veered into upstate New York in June. The show was a beefed-up version of the typical American show, featuring a large roster of circus performers, an extensive menagerie, and a sideshow with a French Giant, a skeleton man, etc. These attractions were arranged in separate tents, but they could all be seen with the purchase of one fifty-cent ticket. Seemingly the most unique element of this show was that it featured an “Indian Circus Rider,” Ka-Ke-Wa-Ma, who performed in the center ring. In addition, there was a larger Iroquois Indian Troupe that appeared in a spectacular pantomime called Life in the Wilderness for the show’s finale. Advertisements promised “characteristic scenes and dances,” and a staging of the story of Pocahontas & Captain Smith that featured a “terrible realistic scalping scene.” Part of what is so interesting about this Iroquois Indian Troupe is that it predated Buffalo Bill’s famous Wild West Show by over a decade, but used many of the elements that made that later concern such a success. While Indians had often figured in American show business before, this kind of proto-Wild West entertainment was something of an innovation and was very popular according to press accounts. The newspaper advertisement to the left, from the Jamestown Journal, gives a full run-down of the show. Perhaps the most notable individual performer was Willie O. Dale, billed as the “Wonder Equestrian and bareback sensationalist.” Though just twelve or thirteen years old, he had been trained by his father of the same name, who was regarded as one of the finest equestrian performers of his era. Dale’s act consisted of various dramatic balancing and acrobatic feats performed on the back of a moving horse, most notably backwards somersaults. The fact that the Ring Master Robert Ellingham was also listed as a “Lecturer on Natural History,” suggests that the well-appointed menagerie played a prominent role in the show. Indeed, much of the show’s advertising centered on the animals, even if many of those pictured in the posters do not seem to have actually been present on the lot.

Whatever the case, George G. Gordon was certainly traveling with the show that year, at least until it passed through East Aurora, which is about twenty miles southeast of Buffalo. Legend has it that Gordon was a performer who fell off a horse, but a more reliable account suggests that he was simply a foreman of a tent crew who suffered heart attack while the big top was being raised. His elaborate tombstone was most likely purchased through funds donated by his fellow circus hands. An 1875 account in the New York Clipper noted that when the Van Amburgh circus visited East Aurora on July 31: “the members of the company and band visited the grave of George G. Gordon, who died while in the employ of the Central Park Circus, and had formerly been a watchman with Van Amburgh & Co. Many citizens were also in attendance, and appropriate remarks and a prayer were made by Rev. Mr. Adams.” Gordon was clearly well-regarded, and the story goes that a circus lady asked local children to plant flowers on his grave every spring, which became a tradition through the 1960s.

But “the show most go on” as they say, and the Great Central Park Menagerie and Circus continued its 1872 tour through Pennsylvania and New Jersey, ending its season in New York City that October. The show foundered the following year as the Panic of 1873 proved a disaster for the American circus industry and sunk many of the big wagon shows. The properties, animals, and many of the performers were subsequently absorbed into the Great London Show, which toured by railroad in 1874. Although they were both ultimately short-lived, George G. Gordon’s magnificent tombstone stands as a memorial to both the man and the Central Park Circus and Menagerie.